Mastering the Difference Between Accounts Payable and Receivable: A Complete Guide for Finance Professionals

A payment deadline approaches, but the expected funds from a client remain unpaid. At the same time, vendors begin sending reminders for invoices nearing their due dates. These are not rare events; they are daily realities for finance teams managing the delicate balance between incoming and outgoing funds. Understanding the difference between accounts payable and accounts receivable is not simply a matter of definitions. It directly influences cash flow health, financial planning, and the operational stability of any organization.

This article explores the distinctions, examples, and key metrics every finance professional must master to maintain control over this financial equilibrium.

What Are Accounts Payable (AP)?

Accounts payable refers to the short-term financial obligations a company owes to its suppliers, vendors, or service providers. These are amounts due for goods or services received but not paid for yet. Recorded as a liability on the balance sheet, accounts payable represent the company’s commitment to pay its creditors within a specified timeframe, typically 30 to 90 days. Managing accounts payable efficiently ensures that obligations are met without compromising cash flow or supplier relationships. Examples of Accounts Payable:

- A retail store orders inventory from a wholesaler and receives the invoice with 60-day payment terms.

- A company contracts a cleaning service for its office and receives a monthly invoice.

- A construction firm buys raw materials on credit for a project and agrees to pay within 45 days.

In each case, the company incurs an obligation to pay, which is recorded as accounts payable until the amount is settled.

What Are Accounts Receivable (AR)?

Accounts receivable represent the amounts a company is owed by its customers for goods delivered or services rendered on credit. It is recorded as an asset on the balance sheet, as it reflects future economic benefits expected from customers. Maintaining healthy accounts receivable is crucial for sustaining liquidity, particularly in businesses where sales are made on credit terms frequently. Examples of Accounts Receivable:

- A software company extends an annual subscription service and bills customers upfront, giving them 30 days to pay.

- A graphic design agency completes a project for a client and issues an invoice for payment within 15 days.

- A manufacturer delivers products to a distributor and offers a 90-day credit term.

These amounts are recorded as accounts receivable and represent anticipated inflows that support the company’s working capital.

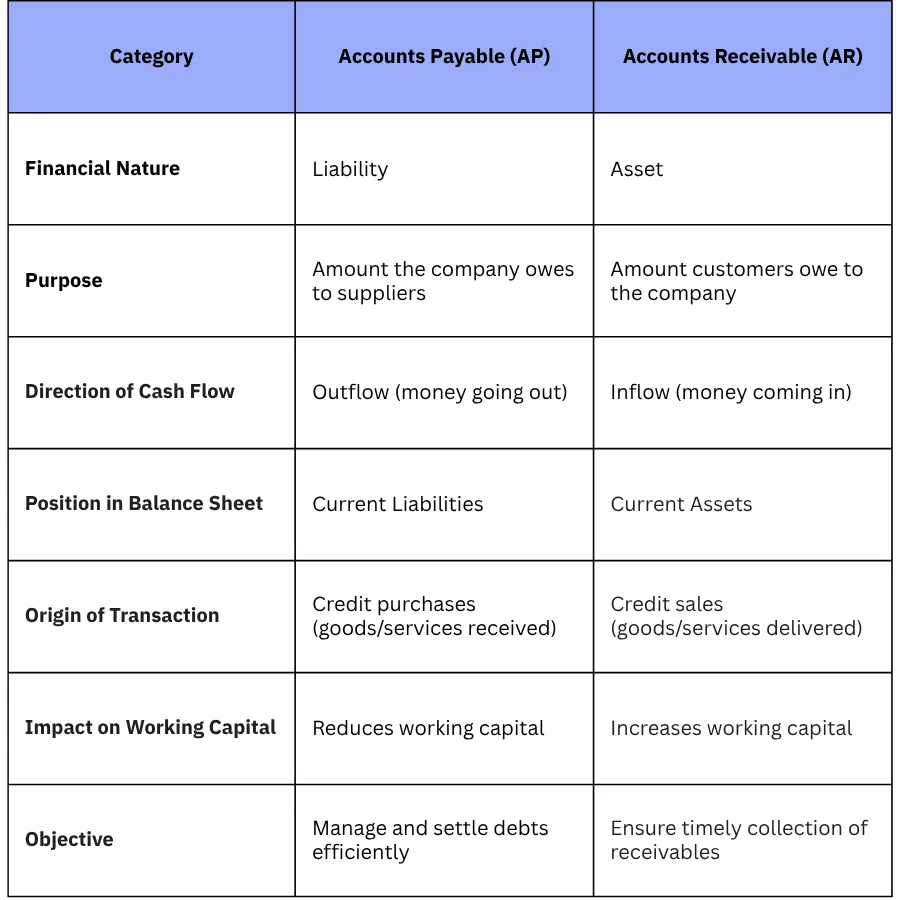

Key Differences Between Accounts Payable and Accounts Receivable

Understanding the differences between accounts payable (AP) and accounts receivable (AR) is major for accurate financial reporting, cash flow control, and decision-making. Though they are closely related, they serve opposite functions in the accounting cycle.

Accounts Receivable Turnover Ratio

The Accounts Receivable Turnover Ratio measures how efficiently a company collects its receivables over a specific period. It indicates how many times the company converts its credit sales into cash. A higher ratio reflects effective credit management and faster collection cycles, while a lower ratio may signal issues in collecting customer payments.

Why is Accounts Receivable Turnover Ratio Important?

This ratio is especially important for companies that rely heavily on credit sales. Monitoring it regularly helps maintain healthy cash flow and minimize bad debt risk, as it:

- Helps evaluate the liquidity of receivables.

- Indicates how quickly a company converts credit sales to cash.

- Assists in identifying collection inefficiencies.

- Useful for setting or reviewing credit policies.

How to Calculate the Accounts Receivable Turnover Ratio

Understanding how often a company collects payments from its customers is essential for assessing credit efficiency and cash flow stability. The accounts receivable turnover ratio provides a clear, numerical indicator of how effectively receivables are managed.

Formula:

Formula:

Accounts Receivable Turnover Ratio =

Average Accounts Receivable ـــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــ

Net Credit Sales

Accounts Receivable Turnover Ratio's Formula Components:

- Net Credit Sales: Total credit sales during the period (excluding cash sales and returns).

- Average Accounts Receivable =(BeginningAR+EndingAR)÷2

If a company has SAR 500,000 in net credit sales during the year, and its average accounts receivable is SAR 100,000:

If a company has SAR 500,000 in net credit sales during the year, and its average accounts receivable is SAR 100,000:

Ratio= 100,000 ÷ 500,000 =5

This means the company collects its receivables 5 times per year.

What Does the Accounts Receivable Turnover Ratio Tell You?

The value of the ratio helps finance teams understand how efficiently the company is converting its receivables into cash. Here's how to interpret it:

- High Ratio: Indicates that the company is collecting receivables quickly. This may reflect strong credit policies and efficient debt collection practices. However, if the ratio is too high, it could suggest overly strict credit terms that might discourage potential customers.

- Low Ratio: Suggests that receivables are being collected slowly. This may refer to weak credit policies, inadequate collection procedures, or customers struggling with payments. A low ratio may result in cash flow issues and an increased risk of bad debts.

Why Is This Ratio Useful for Financial Decision-Making?

The ratio is also essential in external financial analysis, as investors and lenders often review it to assess a company’s operational efficiency and credit risk. Finance and accounting teams can use this ratio to:

- Evaluate the effectiveness of credit control and collection teams.

- Set or revise credit terms based on payment behavior.

- Compare performance across periods or with industry benchmarks.

- Monitor cash flow cycles and adjust budgets accordingly.

- Identify potential liquidity problems early.

What Is the Accounts Payable Turnover Ratio?

The Accounts Payable Turnover Ratio measures how frequently a company pays its suppliers during a specific period. It reflects how well a business manages its short-term obligations and vendor relationships. A high turnover ratio indicates that the company pays off its suppliers quickly, while a low ratio may suggest delayed payments or potential liquidity issues.

Why Is the AP Turnover Ratio Important?

This ratio is crucial in industries with high inventory turnover or regular purchasing activity.

- Assesses the company’s ability to meet its short-term liabilities.

- Provides insights into vendor relationship management.

- Helps monitor cash flow and optimize payment cycles.

- Signals financial health and operational efficiency.

How to Calculate the Accounts Payable Turnover Ratio

Formula:

Formula:

Accounts Payable Turnover Ratio =

Cost of Goods Sold (COGS) ـــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــ

Average Accounts Payable

Accounts Payable Turnover Ratio's Formula Components:

- COGS: Represents the direct costs associated with producing goods sold during the period.

- Average Accounts Payable= BeginningAP+EndingAP)÷2

Example:

Example:

If a company has SAR 750,000 in COGS and an average accounts payable of SAR 150,000:

- Ratio= 750,000 ÷ 150,000= 5

This means the company pays its suppliers 5 times per year.

Importance of Managing Both AP and AR

Efficient management of both accounts payable (AP) and accounts receivable (AR) is crucial for sustaining liquidity, building trust with stakeholders, and maintaining smooth operations. These two components are interconnected; imbalances in one can directly impact the other.

- Cash Flow Optimization A business that collects receivables too slowly but pays suppliers promptly may face cash shortages. Conversely, delaying supplier payments while maintaining quick collections can create short-term liquidity but damage vendor relationships. Balancing both ensures consistent cash availability.

- Financial Planning and Forecasting Accurate tracking of AP and AR helps in projecting cash inflows and outflows. This visibility supports better budgeting, avoids overdrafts, and informs investment decisions.

- Operational Stability Strong AP and AR practices reduce the risk of payment disputes, delays, and financial surprises. They contribute to a healthier working capital position, which supports day-to-day operations and long-term growth.

- Creditworthiness and Reputation Timely payments to suppliers and consistent customer collections enhance the company’s reputation and strengthen its credit profile, which are key factors for obtaining loans or supplier financing.

The Role of Accounts Payable and Receivable in the Accounting Cycle

Accounts payable and accounts receivable play fundamental roles in the accounting cycle, influencing journal entries, ledger updates, and ultimately, the accuracy of financial reporting. Both are reflected in the general ledger, categorized under current liabilities (AP) and current assets (AR). At the end of the period, their balances are adjusted, reconciled, and reported in the financial statements.

Journal Entry Flow

These entries must follow accrual accounting principles, ensuring that revenue and expenses are matched with the periods in which they occur, not when cash is exchanged.

When recording AP, entries typically debit the relevant expense or inventory account and credit accounts payable.

Accounts Payable – Journal Entry Example

Accounts Payable – Journal Entry Example

Scenario:

A company receives SAR 10,000 worth of office supplies from a vendor on credit.

- Journal Entry:

Debit Credit

Office Supplies Expense 10,000

Accounts Payable 10,000

(To record office supplies received on credit)

- If the company later pays the supplier:

Debit Credit

Accounts Payable 10,000

Cash 10,000

(To record payment to supplier)

For AR, the company debits accounts receivable and credits revenue or sales.

Accounts Receivable – Journal Entry Example

Accounts Receivable – Journal Entry Example

Scenario:

A company sells SAR 15,000 worth of services to a client on credit.

- Journal Entry: Debit Credit

Accounts Receivable 15,000

Service Revenue 15,000

(To record services sold on credit)

- When the client makes a payment:

Debit Credit

Cash 15,000

Accounts Receivable 15,000

(To record cash received from the customer)

Closing and Reporting

At the end of each accounting period, AP and AR balances are included in the Trial balances, Balance sheets, and Cash flow statements (indirect method). Adjustments may include bad debt provisioning (for AR) and accruals (for AP), both of which impact reported profitability and liquidity.

At the end of each accounting period, AP and AR balances are included in:

Common Mistakes and Operational Risks in Managing Payables and Receivables

Mismanagement of accounts payable and receivable leads to cash flow disruption, delayed reporting, and even supplier or customer dissatisfaction. Below are the most common pitfalls finance teams encounter, and how to resolve them:

- Delayed Invoice Recording Late recording of AP or AR causes inaccurate reporting and late payments or collections. Using an automated accounting software like Wafeq helps to log all invoices immediately upon creation or receipt.

- Duplicate or Missing Invoices Manual processes often lead to double entries or lost invoices, so it's important to implement invoice matching and centralized invoice tracking systems.

- Weak Follow-Up on AR Collections Delayed collections lead to cash shortages and higher bad debt risk. Setting automated reminders, monitoring aging reports, and assigning collection responsibilities are the solutions.

- Poor Communication with Vendors or Clients Unclear payment terms or disputes delay settlements. Using clear contracts and issue statements regularly to customers and suppliers.

- No Reconciliation Process Without monthly reconciliation, discrepancies between AP/AR records and actual payments go unnoticed. Reconcile statements regularly to detect errors or fraud early.

Essential Internal Controls for Accounts Payable and Receivable Management

Implementing strong internal controls around AP and AR is critical for accuracy, fraud prevention, and financial transparency. Below are key controls that every finance team should adopt:

- Segregation of Duties Dividing responsibilities between invoice creation, approval, and reconciliation ensures no single person controls the full transaction, which minimizes the risk of undetected errors or fraud.

- Multi-Level Approval Workflows Establishing structured approval layers for issuing payments, setting credit limits, or approving large invoices adds oversight and helps enforce spending authority and compliance policies.

- Invoice Matching and Verification Enforcing a three-way match between the purchase order, invoice, and goods received note before making a payment ensures accuracy and prevents duplicate or incorrect disbursements.

- Customer Credit Checks Conducting credit evaluations before extending payment terms helps reduce bad debt exposure and ensures that credit decisions are based on data, not assumptions.

- Monthly Reconciliation Regularly reconciling AP and AR subledgers with the general ledger helps maintain up-to-date records and ensures that errors are caught before closing financial periods.

- Audit Trails and Role-Based Access Accounting systems should log all actions taken by users and enforce access permissions by role, ensuring accountability, traceability, and data integrity across the system.

How to Use Aging Reports to Track Outstanding Payables and Receivables

Aging reports are essential tools that categorize outstanding receivables or payables by the time length they have been overdue. These reports help finance teams monitor cash flow, prioritize collections or payments, and assess the business's financial health.

- Accounts Receivable Aging Report This report lists unpaid customer invoices and organizes them by age, typically within 0–30 days, 31–60 days, 61–90 days, and over 90 days. It helps identify which clients are consistently late and supports collection strategies such as follow-ups, credit holds, or escalation. A growing balance in the over-90-days column is often a warning sign of potential bad debts.

- Accounts Payable Aging Report Similar to AR aging, this report groups outstanding supplier invoices by due date. It allows companies to prioritize payments, take advantage of early payment discounts, and avoid late fees. It also helps negotiate better terms with suppliers by demonstrating payment discipline.

Benefits of Aging Reports

These reports provide real-time visibility into the timing and risk of cash inflows and outflows. They support credit policy decisions, help estimate allowances for doubtful accounts, and are often requested in audits or loan assessments. Finance teams can use aging data to reduce overdue balances and maintain positive working capital.

How to Account for Doubtful and Bad Debts in Receivables

Not all receivables turn into cash. Businesses must be prepared for the possibility that some customers will default on payments. To reflect this risk accurately in the financial statements, companies apply the provision for doubtful debts, which estimates the portion of accounts receivable that may not be collected.

What Is a Provision for Doubtful Debts?

It is an estimated allowance recorded in the books to anticipate potential non-payments from customers. It is a key principle under accrual accounting that ensures revenues are not overstated. The provision is usually based on historical trends, customer risk profiles, and aging report analysis.

This provision allows companies to present a more realistic picture of expected cash inflows and prepare for financial shocks. It also improves decision-making when evaluating new credit limits, and it’s often required for compliance with accounting standards like IFRS 9.

How Provision for Doubtful Debts is Recorded in the Accounting System

The standard entry involves debiting a bad debt expense account and crediting allowance for doubtful accounts, a contra-asset that reduces the net accounts receivable figure on the balance sheet. If a debt is later confirmed as uncollectible, it is written off by debiting the allowance and crediting accounts receivable.

Example: Journal Entry for Provision for Doubtful Debts

Example: Journal Entry for Provision for Doubtful Debts

At the end of the year, a company estimates that SAR 5,000 of its accounts receivable may not be collectible, based on historical data and aging analysis.

- Adjusting Journal Entry (to record the provision):

Debit Credit

Bad Debt Expense 5,000

Allowance for Doubtful Accounts 5,000

(To record estimated uncollectible receivables)

- Subsequent Entry (if a specific customer balance of SAR 2,000 is confirmed as uncollectible):

Debit Credit

Allowance for Doubtful Accounts 2,000

Accounts Receivable 2,000

(To write off confirmed bad debt from a customer)

How to Use Supplier Payment Terms and Discounts to Improve Cash Flow

Effectively managing supplier terms is essential for balancing cash outflows while maintaining strong vendor relationships. Many suppliers offer early payment discounts as an incentive for prompt settlement, which can lead to meaningful cost savings if used strategically.

- Understanding Common Terms (e.g., 2/10, Net 30) A term like 2/10, net 30 means the buyer can deduct 2% from the invoice total if payment is made within 10 days; otherwise, the full amount is due within 30 days. Taking advantage of this can significantly reduce procurement costs over time.

- Evaluating Whether to Pay Early Early payment isn’t always ideal; companies should compare the value of the discount to the opportunity cost of using cash earlier. Early payment is beneficial if the discount offers a higher return than keeping cash on hand (e.g., for investment or working capital).

- Negotiating Flexible Payment Terms Extending payment terms (e.g., within 30 to 45 or 60 days) can free up short-term liquidity for businesses with tight cash flow. Open communication with suppliers and a history of timely payments often help negotiate more favorable terms.

- AP Automation Tools Platforms like Wafeq support automation of due dates, discount tracking, and alerts for early payment windows—helping finance teams seize available savings without manual effort.

Essential KPIs to Measure the Performance of Payables and Receivables

Measuring performance using KPIs is essential for understanding how effectively a company manages its receivables and payables. These indicators help track collection efficiency, payment discipline, and liquidity risks.

- Days Sales Outstanding (DSO) DSO measures the average number of days it takes to collect receivables after a sale. A higher DSO may indicate delayed collections and potential cash flow issues. Lower DSO reflects faster cash recovery and better customer credit control.

- Days Payable Outstanding (DPO) DPO reflects the average time a company takes to pay its suppliers. An optimal DPO balances cash retention with supplier relationships. A very high DPO might strain vendor trust, while a very low DPO may indicate missed opportunities for strategic cash management.

- Receivables Turnover Ratio This ratio shows how many times a company collects its average receivables during a period. A high turnover rate implies effective collections, while a low rate suggests weak credit controls or slow-paying customers.

- Payables Turnover Ratio It indicates how often a company pays off its suppliers during a period. A high turnover rate may show good payment discipline, but could also mean limited credit use. A lower rate may reflect reliance on vendor financing or slow cash flow.

- Aging Report Distribution Analyzing the aging distribution of both AP and AR gives deeper insight into how receivables are collected and how liabilities are settled. Consistently aging debts can point to inefficiencies or weak credit policies.

Also Read: Accrual Accounting Essentials: Prepaid Expenses, Accruals, and Revenue Deferrals Explained

Accounts payable and accounts receivable are fundamental components of business finance that require careful management to maintain healthy cash flow and strong supplier and customer relationships. Understanding the differences between these two areas helps professionals optimize workflows, prevent errors, and reduce financial risks.

Effective management relies on clear processes, robust internal controls, timely reconciliations, and key performance indicators used to monitor performance. Tools like aging reports and provisions for doubtful debts further enhance visibility and risk management.

Streamline your accounts payable and receivable with Wafeq. Gain automation, real-time insights, and better financial control.

Streamline your accounts payable and receivable with Wafeq. Gain automation, real-time insights, and better financial control.

.png?alt=media)